The quote is from Avatar (Cameron, 2009), by the way. Not one of my favorite movies, but my vote for James Cameron's second best movie after the first Terminator. (Yes, better than Aliens or Titanic. But, for me, that's not saying much.)

Sunday, May 16, 2010

"One life ends, another begins."

In celebration of my new job at Houston Baptist University (and my new MacBook Pro), I have moved my blog over to Wordpress. Same deal, new location. See you there...

Saturday, July 18, 2009

"What is a saint anyway?"

It's been a month since I posted on this blog. During that time I've been moving (from Berkeley back to L.A.) and running an emerging church chapel in the midst of the exhibition hall at the General Convention of the Episcopal Church.

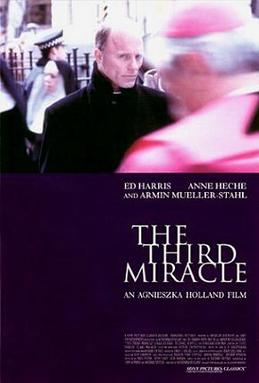

It's been a month since I posted on this blog. During that time I've been moving (from Berkeley back to L.A.) and running an emerging church chapel in the midst of the exhibition hall at the General Convention of the Episcopal Church.You may have seen news reports about the Episcopal Church's controversial legislation regarding same-sex marriage rites and gay bishops. But one thing you might not have heard about is our new list of "saints". The Episcopal Church has always had an unusual understanding of sainthood. The movie The Third Miracle (Holland 1999) is a meditation on sainthood. When someone asks the main character (a priest played by Ed Harris) "What is a saint anyway?", he answers "A saint is a person who is with God in heaven. If you pray to that person and your prayers are answered that means that person has a special connection with God." So the Catholic Church looks for miracles to prove that a person is in heaven and has a special relationship with God. The Episcopal Church, however, is a Protestant church that rejects priestly mediation and hierarchy. We think all Christians have a direct connection to God and can be sure they are going to heaven.

To be fair to The Third Miracle, this might be the point of the film. The representative of the Church hierarchy says "We live in a fallen world. Martyrdom, the great act of faith, seems impossible. Therefore, acts of simple goodness, a soup kitchen, kindness to the poor, have come to seem worthy of saint. But true sainthood is of another world. ... A saint loves God beyond the ordinary human power to love God." But the film presents him as unreliable and hypocritical, suggesting that there can be such a thing as an ordinary saint.

In any event, the Episcopal Church recognizes ordinary saints. We remember people for their contribution to the life of the Church, even if they did not demonstrate any "heroic virtue". In other words, most of our saints are along the lines of what Roman Catholics call "Doctors of the Church".

But unlike the Catholic "doctors", we do not limit our saints to theologians. We recognize artists and scientists as saints, too. For example, poets George Herbert and John Donne were already saints. At the last convention, we added C.S. Lewis. This year we added writers John Bunyan and G.K. Chesterton, composers Bach, Handel, Purcell, William Byrd, and Thomas Tallis, hymn writers Fanny Crosby and Isaac Watts, artists Albrecht Durer, Matthias Guenewald, and Andrei Rublev, and scientists Copernicus and Kepler.

Moreover, if you didn't notice from the above list, the Episcopal Church is unlike most churches in that we recognize saints outside our own tradition. For example, joining the likes of Martin Luther and Dietrich Bonheoffer, this year we added John Calvin, Karl Barth, Thomas Merton, and John of the Cross.

Finally, we let in philosophers. Joining Augustine, Aquinas, Berkeley, and Joseph Butler, we now have Soren Kierkegaard.

St. Clive? (as in Clive Staples Lewis) St. Kierkegaard? These are saints who inspire me to heroic virtue!

Labels:

Episcopal Church,

saints,

The Third Miracle,

theology

Wednesday, June 17, 2009

"The medium is the message."

Here is an interesting audio interview with Todd Bouldin, founder of Pepperdine University's MFA in Screenwriting. I disagree with Bouldin's theory of the Church's relationship to the secular culture, but the interview did make me realize something. Bouldin started out wanting to make an "impact" for Christ in law and politics and then decided that the media is a more important influence on American culture. This connection between politics and the media helped me see what has been bothering me about the typical theory of how Christians should relate to Hollywood.

In the interview, Bouldin expresses a viewpoint similar to H. Richard Niebuhr. Niebuhr rejected what he called the “Christ-against-culture” position in favor of “Christ-transforming-culture” position. (The fun pictures to the left come from this blog post.) This move has become the party line for Evangelicals in Hollywood. The claim is that Christians in the middle part of the 20th Century rejected involvement with secular culture as sinful. But, having been abandoned by Christians and left to their own secular devices, the centers of culture like Hollywood, Washington DC, and Harvard, only got worse and worse and eventually dragged down all of America with them. According to this narrative, the only hope for redeeming American culture is for Evangelical Christians to move from cultural non-engagement to engagement – from Christ-against-culture to Christ-transforming-culture.

In the interview, Bouldin expresses a viewpoint similar to H. Richard Niebuhr. Niebuhr rejected what he called the “Christ-against-culture” position in favor of “Christ-transforming-culture” position. (The fun pictures to the left come from this blog post.) This move has become the party line for Evangelicals in Hollywood. The claim is that Christians in the middle part of the 20th Century rejected involvement with secular culture as sinful. But, having been abandoned by Christians and left to their own secular devices, the centers of culture like Hollywood, Washington DC, and Harvard, only got worse and worse and eventually dragged down all of America with them. According to this narrative, the only hope for redeeming American culture is for Evangelical Christians to move from cultural non-engagement to engagement – from Christ-against-culture to Christ-transforming-culture.

But while Evangelicals in Hollywood are still following this party line, many Evangelicals in Washington have changed their view. (I’m not sure about the Harvard folk.) The difference seems to be that Evangelicals haven’t yet tasted any real power in secular media, but they have in politics. The United States had an Evangelical president. There’s nowhere else to go from there. But despite having achieved genuine power (not just the presidency, but many other influential governmental positions), Evangelicals have failed to transform culture. America is just as godless as ever – maybe more so. Some of the founders of the Religious Right have now admitted that they were “blinded by might” and corrupted by the power they achieved. (Here is a nice summary of this theory.) Instead of the Church transforming culture, culture transformed the Church. Baby boomer Evangelicals still seem intent on the old model (witness Sarah Palin), but younger evangelicals seem to understand the failure of their parents’ ideas (they voted for Obama). Many young people are leaving politics behind for direct engagement with the world. They’re less interested in top down transformation of culture than bottom up revolution. Why bother with ineffective politicians when we can, for example, make a real economic difference by living and working in the inner city?

But while Evangelicals in Hollywood are still following this party line, many Evangelicals in Washington have changed their view. (I’m not sure about the Harvard folk.) The difference seems to be that Evangelicals haven’t yet tasted any real power in secular media, but they have in politics. The United States had an Evangelical president. There’s nowhere else to go from there. But despite having achieved genuine power (not just the presidency, but many other influential governmental positions), Evangelicals have failed to transform culture. America is just as godless as ever – maybe more so. Some of the founders of the Religious Right have now admitted that they were “blinded by might” and corrupted by the power they achieved. (Here is a nice summary of this theory.) Instead of the Church transforming culture, culture transformed the Church. Baby boomer Evangelicals still seem intent on the old model (witness Sarah Palin), but younger evangelicals seem to understand the failure of their parents’ ideas (they voted for Obama). Many young people are leaving politics behind for direct engagement with the world. They’re less interested in top down transformation of culture than bottom up revolution. Why bother with ineffective politicians when we can, for example, make a real economic difference by living and working in the inner city?

What we are seeing is that Niebuhr’s categories are misleading. Everyone – even those like Tertullian, Tolstoy, and the Quakers who Niebuhr cites as paradigmatic defenders of the Christ-against-culture position – want to transform culture. The question is not should we transform culture, but how can we transform it. The Christ-against-culture position rejects the idea – held by the Christ-tranforming-culture position – that Christians can use the tools of cultural power (e.g., politics, the arts, higher education, etc.) to transform culture. Rather the Christ-against-culture position holds that the Church has its own tools and its own very different understanding of power. On this view, whenever the Church attempts to use the world’s tools, the Church only succeeds in transforming itself into the world. For example, when the Church uses advertising techniques to market itself, it positions itself as just another product to be consumed and ceases to be an alternative to consumer culture. This is what Marshall McLuhan was talking about about when he said “The medium is the message.”

Unfortunately Evangelicals in Hollywood haven’t learned the lessons of Evangelical engagement in politics. Evangelicals still dream of “impacting” Hollywood by lifestyle evangelism (as Bouldin says, “simply being there”). The assumption of this strategy is that if individual filmmakers “get saved”, then culture will change. The problem is that it won’t work. If getting the President of the United States saved couldn’t transform American culture, then why think getting the president of Disney saved would work better? It is mystifying to me that Bouldin could understand that politics can’t transform culture but think the media can.

What if we give up pursuit of Hollywood power for the kind of direct engagement in the world that young people are discovering in the political realm? This would look like making independent films by, for, and about Christians. I’m not recommending cheesy evangelistic movies of the past, but serious (both dramatic and comic) artistic engagement with the issues that matter to us but which secular filmmakers simply can’t understand. What we need is a Christian version of Spike Lee who makes excellent art by, for, and about, African-Americans. This is a Christ-against-culture position. But it is not a call to hide in some self-imposed Christian ghetto. We shouldn’t create a parallel Christian movie studio. That would be like rejecting both the Democrats and the Republicans to create a third party for Christians. Instead we should -- if we want to transform American culture – reject politics/Hollywood altogether and do something entirely new.

There’s nothing wrong with working in Hollywood or Washington, DC as long as we don’t fool ourselves into thinking that we’re secret missionaries who will have some sort of “impact”. True transformation will have to come from a more radical strategy, the strategy of the Cross. Politics is all about power, but the Cross repudiates power in favor of weakness. That’s why Jesus says thinks like “My Kingdom is not of this world” and “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s”. You might be able to be a Christian who is involved in politics, but you can’t be a Christian politician who uses the tools of Washington to further the cause of Christ. Similarly, the media is all about money, but the Cross reveals money to be an idol. That’s why Jesus says things like “You can’t serve God and money” and “Sell all you own, give to the poor, and follow me.” Again, you might be able to be a Christian who works in Hollywood, but you can’t be a Christian filmmaker who uses the tools of Hollywood to further the cause of Christ.

Am I wrong? Please let me know by posting a comment. I welcome any friendly criticism you can offer.

In the interview, Bouldin expresses a viewpoint similar to H. Richard Niebuhr. Niebuhr rejected what he called the “Christ-against-culture” position in favor of “Christ-transforming-culture” position. (The fun pictures to the left come from this blog post.) This move has become the party line for Evangelicals in Hollywood. The claim is that Christians in the middle part of the 20th Century rejected involvement with secular culture as sinful. But, having been abandoned by Christians and left to their own secular devices, the centers of culture like Hollywood, Washington DC, and Harvard, only got worse and worse and eventually dragged down all of America with them. According to this narrative, the only hope for redeeming American culture is for Evangelical Christians to move from cultural non-engagement to engagement – from Christ-against-culture to Christ-transforming-culture.

In the interview, Bouldin expresses a viewpoint similar to H. Richard Niebuhr. Niebuhr rejected what he called the “Christ-against-culture” position in favor of “Christ-transforming-culture” position. (The fun pictures to the left come from this blog post.) This move has become the party line for Evangelicals in Hollywood. The claim is that Christians in the middle part of the 20th Century rejected involvement with secular culture as sinful. But, having been abandoned by Christians and left to their own secular devices, the centers of culture like Hollywood, Washington DC, and Harvard, only got worse and worse and eventually dragged down all of America with them. According to this narrative, the only hope for redeeming American culture is for Evangelical Christians to move from cultural non-engagement to engagement – from Christ-against-culture to Christ-transforming-culture. But while Evangelicals in Hollywood are still following this party line, many Evangelicals in Washington have changed their view. (I’m not sure about the Harvard folk.) The difference seems to be that Evangelicals haven’t yet tasted any real power in secular media, but they have in politics. The United States had an Evangelical president. There’s nowhere else to go from there. But despite having achieved genuine power (not just the presidency, but many other influential governmental positions), Evangelicals have failed to transform culture. America is just as godless as ever – maybe more so. Some of the founders of the Religious Right have now admitted that they were “blinded by might” and corrupted by the power they achieved. (Here is a nice summary of this theory.) Instead of the Church transforming culture, culture transformed the Church. Baby boomer Evangelicals still seem intent on the old model (witness Sarah Palin), but younger evangelicals seem to understand the failure of their parents’ ideas (they voted for Obama). Many young people are leaving politics behind for direct engagement with the world. They’re less interested in top down transformation of culture than bottom up revolution. Why bother with ineffective politicians when we can, for example, make a real economic difference by living and working in the inner city?

But while Evangelicals in Hollywood are still following this party line, many Evangelicals in Washington have changed their view. (I’m not sure about the Harvard folk.) The difference seems to be that Evangelicals haven’t yet tasted any real power in secular media, but they have in politics. The United States had an Evangelical president. There’s nowhere else to go from there. But despite having achieved genuine power (not just the presidency, but many other influential governmental positions), Evangelicals have failed to transform culture. America is just as godless as ever – maybe more so. Some of the founders of the Religious Right have now admitted that they were “blinded by might” and corrupted by the power they achieved. (Here is a nice summary of this theory.) Instead of the Church transforming culture, culture transformed the Church. Baby boomer Evangelicals still seem intent on the old model (witness Sarah Palin), but younger evangelicals seem to understand the failure of their parents’ ideas (they voted for Obama). Many young people are leaving politics behind for direct engagement with the world. They’re less interested in top down transformation of culture than bottom up revolution. Why bother with ineffective politicians when we can, for example, make a real economic difference by living and working in the inner city?What we are seeing is that Niebuhr’s categories are misleading. Everyone – even those like Tertullian, Tolstoy, and the Quakers who Niebuhr cites as paradigmatic defenders of the Christ-against-culture position – want to transform culture. The question is not should we transform culture, but how can we transform it. The Christ-against-culture position rejects the idea – held by the Christ-tranforming-culture position – that Christians can use the tools of cultural power (e.g., politics, the arts, higher education, etc.) to transform culture. Rather the Christ-against-culture position holds that the Church has its own tools and its own very different understanding of power. On this view, whenever the Church attempts to use the world’s tools, the Church only succeeds in transforming itself into the world. For example, when the Church uses advertising techniques to market itself, it positions itself as just another product to be consumed and ceases to be an alternative to consumer culture. This is what Marshall McLuhan was talking about about when he said “The medium is the message.”

Unfortunately Evangelicals in Hollywood haven’t learned the lessons of Evangelical engagement in politics. Evangelicals still dream of “impacting” Hollywood by lifestyle evangelism (as Bouldin says, “simply being there”). The assumption of this strategy is that if individual filmmakers “get saved”, then culture will change. The problem is that it won’t work. If getting the President of the United States saved couldn’t transform American culture, then why think getting the president of Disney saved would work better? It is mystifying to me that Bouldin could understand that politics can’t transform culture but think the media can.

What if we give up pursuit of Hollywood power for the kind of direct engagement in the world that young people are discovering in the political realm? This would look like making independent films by, for, and about Christians. I’m not recommending cheesy evangelistic movies of the past, but serious (both dramatic and comic) artistic engagement with the issues that matter to us but which secular filmmakers simply can’t understand. What we need is a Christian version of Spike Lee who makes excellent art by, for, and about, African-Americans. This is a Christ-against-culture position. But it is not a call to hide in some self-imposed Christian ghetto. We shouldn’t create a parallel Christian movie studio. That would be like rejecting both the Democrats and the Republicans to create a third party for Christians. Instead we should -- if we want to transform American culture – reject politics/Hollywood altogether and do something entirely new.

There’s nothing wrong with working in Hollywood or Washington, DC as long as we don’t fool ourselves into thinking that we’re secret missionaries who will have some sort of “impact”. True transformation will have to come from a more radical strategy, the strategy of the Cross. Politics is all about power, but the Cross repudiates power in favor of weakness. That’s why Jesus says thinks like “My Kingdom is not of this world” and “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s”. You might be able to be a Christian who is involved in politics, but you can’t be a Christian politician who uses the tools of Washington to further the cause of Christ. Similarly, the media is all about money, but the Cross reveals money to be an idol. That’s why Jesus says things like “You can’t serve God and money” and “Sell all you own, give to the poor, and follow me.” Again, you might be able to be a Christian who works in Hollywood, but you can’t be a Christian filmmaker who uses the tools of Hollywood to further the cause of Christ.

Am I wrong? Please let me know by posting a comment. I welcome any friendly criticism you can offer.

Labels:

evangelicalism,

film,

politics,

postmodernism,

theology

Monday, June 1, 2009

"When somebody asks me a question, I tell them the answer."

This weekend I finally got around to seeing last year’s Best Picture winner Slumdog Millionaire (Boyle, 2008). I liked it a lot, but I couldn’t help wondering, “Was this really the best movie of 2008?” My first thought as the film was ending was “That was good, but not as good as Wall-E or The Dark Knight.”

This weekend I finally got around to seeing last year’s Best Picture winner Slumdog Millionaire (Boyle, 2008). I liked it a lot, but I couldn’t help wondering, “Was this really the best movie of 2008?” My first thought as the film was ending was “That was good, but not as good as Wall-E or The Dark Knight.” Now, the Academy certainly shouldn’t be ashamed of honoring Slumdog. It may be a mistake, but its not nearly as embarrassing as giving the award to Forest Gump instead of Pulp Fiction in 1994 or giving the award to movies that are actually bad like Crash in 2006 or Titanic in 1997. This line of thinking got me wondering about how often the Academy has be wrong in recent years. Here’s my list of best pictures in retrospect, all the way back to the biggest recent goof in 1994. In my opinion, the only year the Academy got it right was 2007. (Note that these aren’t necessarily my favorite movies; they’re my vote for the best movies of that year. The only years my favorite movies were also the best movies were 2001 and 2002)

The Best Movies of the Past 15 Years

1994: TIE: Pulp Fiction (Tarantino, 1994) and Three Colors: Red (Kieslowski, 1994)

1995: Toy Story (Lasseter, 1995)

1996: Fargo (Coen, 1996)

1997: Boogie Nights (Anderson, 1997)

1998: The Truman Show (Weir, 1998)

1999: Being John Malkovich (Jonze, 1999)

2000: Memento (Nolan, 2000)

2001: Moulin Rouge! (Luhrmann, 2001)

2002: Adaptation (Jonze, 2002)

2003: Dogville (von Trier, 2003)

2004: Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Gondy, 2004)

2005: The New World (Malick, 2005)

2006: Children of Men (Cuarón, 2006)

2007: No Country For Old Men (Coen, 2007)

2008: The Dark Knight (Nolan, 2008)

Just for fun, here are my favorite movies of the year. For the most part, they are runners-up for the best movies of the year, though some are more like guilty pleasures. (In particular, I’m not sure I can defend the artistic value of Bottle Rocket, Shaun of the Dead, The Prestige, Hot Fuzz, and Speed Racer. I just think they’re a lot of fun to watch.)

1994: The Shawshank Redemption (Darabont, 1994)

1995: 12 Monkeys (Gilliam, 1995)

1996: Bottle Rocket (Anderson, 1996)

1997: Princess Mononoke (Miyazaki, 1997)

1998: The Big Lebowski (Coen, 1998)

1999: TIE: Fight Club (Fincher, 1999) and The Matrix (Wachowski Brothers, 1999)

2000: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Lee, 2000)

2001: Moulin Rouge! (Luhrmann, 2001)

2002: Adaptation (Jonze, 2002)

2003: Kill Bill, Vol. 1 (Tarantino, 2003)

2004: Shaun of the Dead (Wright, 2004)

2005: The Constant Gardner (Meirelles, 2005)

2006: The Prestige (Nolan, 2006)

2007: Hot Fuzz (Wright, 2007)

2008: Speed Racer (Wachowski Brothers, 2008)

And, while I’m making lists, here is my current Top 10 Favorite Movies of All Time. I try to make one of these lists every couple of years, and they inevitably change. (For example, 1 and 2 new on the list this time, having become favorites since I last made a list in 2004,)

1. Babette’s Feast (Axel, 1987)

2. F for Fake (Welles, 1974)

3. Princess Mononoke (Miyazaki, 1997)

4. Adaptation (Jonze, 2002)

5. Pulp Fiction (Tarantino, 1994)

6. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (Stoppard, 1990)

7. The Big Lebowski (Coen, 1998)

8. 12 Monkeys (Gilliam, 1995)

9. The Nightmare Before Christmas (Selick, 1993)

10. The Lord of the Rings (Jackson, 2001-3)

The Best Movies of the Past 15 Years

1994: TIE: Pulp Fiction (Tarantino, 1994) and Three Colors: Red (Kieslowski, 1994)

1995: Toy Story (Lasseter, 1995)

1996: Fargo (Coen, 1996)

1997: Boogie Nights (Anderson, 1997)

1998: The Truman Show (Weir, 1998)

1999: Being John Malkovich (Jonze, 1999)

2000: Memento (Nolan, 2000)

2001: Moulin Rouge! (Luhrmann, 2001)

2002: Adaptation (Jonze, 2002)

2003: Dogville (von Trier, 2003)

2004: Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Gondy, 2004)

2005: The New World (Malick, 2005)

2006: Children of Men (Cuarón, 2006)

2007: No Country For Old Men (Coen, 2007)

2008: The Dark Knight (Nolan, 2008)

Just for fun, here are my favorite movies of the year. For the most part, they are runners-up for the best movies of the year, though some are more like guilty pleasures. (In particular, I’m not sure I can defend the artistic value of Bottle Rocket, Shaun of the Dead, The Prestige, Hot Fuzz, and Speed Racer. I just think they’re a lot of fun to watch.)

1994: The Shawshank Redemption (Darabont, 1994)

1995: 12 Monkeys (Gilliam, 1995)

1996: Bottle Rocket (Anderson, 1996)

1997: Princess Mononoke (Miyazaki, 1997)

1998: The Big Lebowski (Coen, 1998)

1999: TIE: Fight Club (Fincher, 1999) and The Matrix (Wachowski Brothers, 1999)

2000: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Lee, 2000)

2001: Moulin Rouge! (Luhrmann, 2001)

2002: Adaptation (Jonze, 2002)

2003: Kill Bill, Vol. 1 (Tarantino, 2003)

2004: Shaun of the Dead (Wright, 2004)

2005: The Constant Gardner (Meirelles, 2005)

2006: The Prestige (Nolan, 2006)

2007: Hot Fuzz (Wright, 2007)

2008: Speed Racer (Wachowski Brothers, 2008)

And, while I’m making lists, here is my current Top 10 Favorite Movies of All Time. I try to make one of these lists every couple of years, and they inevitably change. (For example, 1 and 2 new on the list this time, having become favorites since I last made a list in 2004,)

1. Babette’s Feast (Axel, 1987)

2. F for Fake (Welles, 1974)

3. Princess Mononoke (Miyazaki, 1997)

4. Adaptation (Jonze, 2002)

5. Pulp Fiction (Tarantino, 1994)

6. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (Stoppard, 1990)

7. The Big Lebowski (Coen, 1998)

8. 12 Monkeys (Gilliam, 1995)

9. The Nightmare Before Christmas (Selick, 1993)

10. The Lord of the Rings (Jackson, 2001-3)

Labels:

best picture,

film,

Slumdog Millionare,

Top 10

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

9

What's with the number 9? I just spent some time looking at movie trailers on the Apple website, and I noticed that this year (2009) we will have movies titled Nine, 9, $9.99, and District 9. What's more they're in my favorite genres: Nine is a musical, 9 and $9.99 are animated, and District 9 is sci-fi. Also Nine is a remake of an art film (Fellini's 8 1/2). And, judging from the trailers, at least two of the movies (9 and District 9) have political themes and the other two are about the meaning of life (Nine and $9.99). It looks like 2009 will be a great year for lovers of film as well as lovers of the number 9.

What's with the number 9? I just spent some time looking at movie trailers on the Apple website, and I noticed that this year (2009) we will have movies titled Nine, 9, $9.99, and District 9. What's more they're in my favorite genres: Nine is a musical, 9 and $9.99 are animated, and District 9 is sci-fi. Also Nine is a remake of an art film (Fellini's 8 1/2). And, judging from the trailers, at least two of the movies (9 and District 9) have political themes and the other two are about the meaning of life (Nine and $9.99). It looks like 2009 will be a great year for lovers of film as well as lovers of the number 9.

Labels:

animation,

film,

meaning of life,

politics,

sci-fi

Friday, May 8, 2009

"To progress by moving backwards"

I was walking down the street the other day and saw someone pushing a Bugaboo Cameleon stroller. Bugaboo is one of the hippest brands of stroller, largely (I think) because it is the most expensive brand. Personally I prefer both Stokke and Quinny strollers. (Both are only slightly less outrageously priced than the Bagaboo. We were lucky enough to get a gently used Quinny for Maggie at half the list price.) But if I had to buy a Bugaboo, I'd go for the "Cameleon" model. In one of its configurations it transforms into an old-school British-style pram. (The Cameleon is pictured to the left, and an antique pram is pictured to the right.)

I was walking down the street the other day and saw someone pushing a Bugaboo Cameleon stroller. Bugaboo is one of the hippest brands of stroller, largely (I think) because it is the most expensive brand. Personally I prefer both Stokke and Quinny strollers. (Both are only slightly less outrageously priced than the Bagaboo. We were lucky enough to get a gently used Quinny for Maggie at half the list price.) But if I had to buy a Bugaboo, I'd go for the "Cameleon" model. In one of its configurations it transforms into an old-school British-style pram. (The Cameleon is pictured to the left, and an antique pram is pictured to the right.)This is great example of retrofuturistic design. I discussed retrofuturism in my earlier post on the movie Steamboy. By the way, the current Wikipedia article on retrofuturism has got it wrong. That article limits the use of the term "retrofuturism" to nostalgic representations of what past eras thought the future would look like. For example, if Old Navy started selling silver jump suits, that would be retrofuturistic. And that is definitely one common use of the term. But, as Wikipedia itself notes, the term was originally coined by conceptual artist Lloyd Dunn who used it to mean "the act or tendency of an artist to progress by moving backwards." Dunn was an early practicioner of what has come to be called mashup in which parts of several existing artworks are combined to form a new artwork. Here is an excellent article about the history of the term, written by people who worked with Dunn. The article explains that:

Retrofuturism is an idiom in which expressions are constructed, as in any natural language, out of pre-existing conventional elements. The machine arts (photography, xerox, audiotape, video, etc.), like the work of the contemporary language poets, coin new "words" like no other media in history. Because they are mechanistically reproductive, they also conventionalize and codify information. Conventionalized material, like the cliché (a form of verbal shorthand which collapses entire narratives, often into a few syllables) becomes the raw material for for the construction of new metalogic expressions. Artworks are also complex, like real words, which have an internal syntax all their own. Retrofuturist artworks do them one better by being like sentences, recursive collections of (themselves) recursive words; all parts of which exhibit syntactic structure (and play with it) to express new thoughts (and old ones in novel juxtapositions).

So in its broadest use "retrofuturism" is just another name for "mashup". In its more common use, retrofuturism means the use of design conventions and clichés from past artistic periods to present something that looks modern, even futuristic. This is the way the Museum of Contemporary Art used the term when it applied it to a show of car designs by J Mays (the artist who designed the new VW Beetle, Ford Mustang, and Ford Thunderbird). (You can read more about the show and see some pictures here. And you can get a good sense of what Mays is doing if you compare the 1955 Thunderbird seen here with the 2002 Thunderbird seen here.) And this is what the Bugaboo pram is doing.

Seeing this retrofuturistic pram also made me realize that this is what the emerging church is doing, too. (See my earlier post on the emerging church and/as avant garde.) Having realized that the church's links to philosophical modernism has left it theologically bankrupt, emerging theologians are attempting to return to premodern ancient and medieval theology for resources in constructing a postmodern theology. (Hence such formulations as "ancient-future faith".) In other words, they are looking to the past to find a way to move forward. In still other words, the emerging church is retrofuturistic religion.

Labels:

art,

emerging church,

Maggie,

retrofuturism,

theology

Wednesday, May 6, 2009

"BSG expressed what we really are: all messed up and barely hanging on."

It's been about six weeks since Ronald D. Moore's remake of Battlestar Galactica (Moore et al, 2003-2009) ended its television run. I have to admit that, depite its defender's hyperbolic claims of greatness, the series left me cold. While I am a fan of science fiction, but I don't feel the need to watch every sci-fi show on TV. I only watch the good ones. And all I can say for Battlestar is that, while it certainly isn't one of the bad ones, it doesn't quite reach the level of the good ones. In that category I would include The Twilight Zone, Star Trek (especially The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine), Twin Peaks, The X-Files, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly, Lost, and Dollhouse. When compared to these shows, Battlestar is just mediocre.

It's been about six weeks since Ronald D. Moore's remake of Battlestar Galactica (Moore et al, 2003-2009) ended its television run. I have to admit that, depite its defender's hyperbolic claims of greatness, the series left me cold. While I am a fan of science fiction, but I don't feel the need to watch every sci-fi show on TV. I only watch the good ones. And all I can say for Battlestar is that, while it certainly isn't one of the bad ones, it doesn't quite reach the level of the good ones. In that category I would include The Twilight Zone, Star Trek (especially The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine), Twin Peaks, The X-Files, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly, Lost, and Dollhouse. When compared to these shows, Battlestar is just mediocre.Battlestar is only a "brilliant" sci-fi show when you compare it to lesser shows such as Stargate, or Heroes. It took me a while to figure out that that's what Battlestar's defenders were doing. Hard core sci-fi geeks are so amazed when a sci-fi show doesn't absolutely suck that they tend to overpraise it. A comment by Geoff Holsclaw over at the Church and Postmodern Culture blog helped me realize what was going one. Holsclaw writes:

Once Firefly was canceled (which still remains unrivaled in my opinion) I thought there would never be redemption for televised science fiction. I thought I was condemned to watching Andromeda or Stargate forever. I thought that I would eternally dwell in a universe created by Gene Roddenberry.

Holsclaw admits that Firefly is far better than Battlestar but then declares the latter great in comparison to crap like Andromeda and Stargate.

But I can't let him get away with his denigration of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. Holsclaw's reason for thinking that Battlestar is better than Star Trek is that the latter was "really just a liberal, multi-cutlural fantasy giving us an image of what we aspired to be as a society without calling us out everything that hindered us." Now, the first half of this statement is true. Star Trek is a fantasy of why liberals aspire society to be. But I disagree that Star Trek didn't criticize liberal society's failings. On the contrary, every alien society the Starship Enterprise encountered was a thinly veiled metaphor for 20th Century Earth. While the future Earth as Star Trek envisioned it was perfect, each of the alien planets had some problem that the Star Trek writers saw in America. The show was specifially designed to critique the failings of our society and point us toward an idealized vision of the future.

As a postmodern Christian I see much to criticize in Star Trek. I think what Holsclaw is Star Trek's liberal assumption that the ideal society would be perfectly godless and secular. But that's not what he explicitly criticizes in Star Trek. He does not criticize its particular vision of the idealized society, rather he attacks the aesthetic of idealization itself:

As someone said, Star Trek was a symbol of what we hoped to be while BSG expressed what we really are: all messed up and barely hanging on. For the most part BSG unflinchingly dealt with the tragic aspect of humanity, that we are simultaneously cylons and humans, uh, I mean sinners and saints.

But I reject his premise that only realistic (as opposed to idealistic) art can be good. Art has both realistic and idealistic functions. Take 80s sit-coms, instead of sci-fi. While it might be important to have sit-coms like Roseanne or The Simpsons which show us a realistic portrait of a messed up family, it is just as important to have sit-coms like The Cosby Show and Family Ties which give us idealized families. An idealized TV family gives us something to aspire to and helps form our moral imaginations with images of what is possible rather than leaving us stuck with our current problems. Maybe no father is as perfect as Bill Cosy's Cliff Huxtable, but that doesn't mean we shouldn't try to live up to that standard.

Note: I blogged about this issue before in my post on Thomas Hibbs's idea that recent Christian artists have failed to imagine a world where goodness is attractive.

Labels:

Battlestar Galactica,

heroes,

philosophy,

sci-fi,

Star Trek,

The Cosby Show,

theology

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)